How we Cope with Grief

- Dr Danielle Baillieu

- Jun 6, 2023

- 7 min read

Grief is the emotional reaction to bereavement; (Archer (1999, p. 5) ) described it as “the cost we pay for being able to love in the way we do” Generally, grief is perceived as a negative, unwanted emotion and can involve a complex myriad of feelings and changes, including cognitive, physical and physiological changes that may vary from person to person and differ depending on country, culture and religion, as well as the context. For instance, death after a long, well-lived life, or long-term illness, can lead to the celebration of what that person has achieved or relief due to the end of their suffering (Stroebe, 2008). However, a sudden or unexpected death through illness or accident can leave loved ones feeling overwhelmed and shattered (Parkes et al., 2013; Stroebe et al., 2008; Worden, 2000). The grief literature has developed over time, with various models emerging. The pioneering work of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross (1970) subsequently led to the emergence of the five stages of grief model: Denial – refusal to accept the loss. The world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. The bereaved may go numb and find it hard to carry on; Anger – the bereaved or dying may feel anger towards themselves or others, including God; Bargaining – this may be bargaining with God to spare your life or bargaining with God to spare a loved one from death; Depression – recognition of the loss. It is an appropriate response to the loss and can Acceptance – accepting that death is going to take place or has taken place. The bereaved can move on from their loss. Kubler-Ross generated her stages model after conducting over 200 interviews over a period of three years (1969) with terminally ill patients. The experiences of terminal illness may not parallel bereavement following the death of a loved one. Indeed. Kübler-Ross herself, towards the end of her life, openly admitted that it was not a universally applicable model, that not everybody experienced the stages in sequence and that not all people experienced every stage.

Other models that are used in therapy today Worden moved away from the “five stages model” and described the more active “tasks of grief” in his model:

Task one, to accept the reality of loss;

Task two,to work through the pain of grief;

Task three, to adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing;

Task four, to emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life.

Bowlby and Parkes’ introduced the Four Phases of Grief Model:

Phase 1: Shock and numbness can last from hours to weeks. There is a sense that the loss is not real and impossible to accept. During this period, there is embodied physical distress.

Phase 2: Yearning and searching for the lost person can last for months or years. The loss leaves a void and a need to fill the emptiness. Phase 3: Despair and disorganisation, including an acceptance that life will never be the same. This may be accompanied by anger and questioning.

Phase 4: Reorganisation and recovery: slowly, there is a realisation that life can still be positive despite the loss. The grief does not disappear, nor is it resolved; it simply recedes, rather than staying at the forefront of the mind.

Stroebe and Schut Dual Process Model

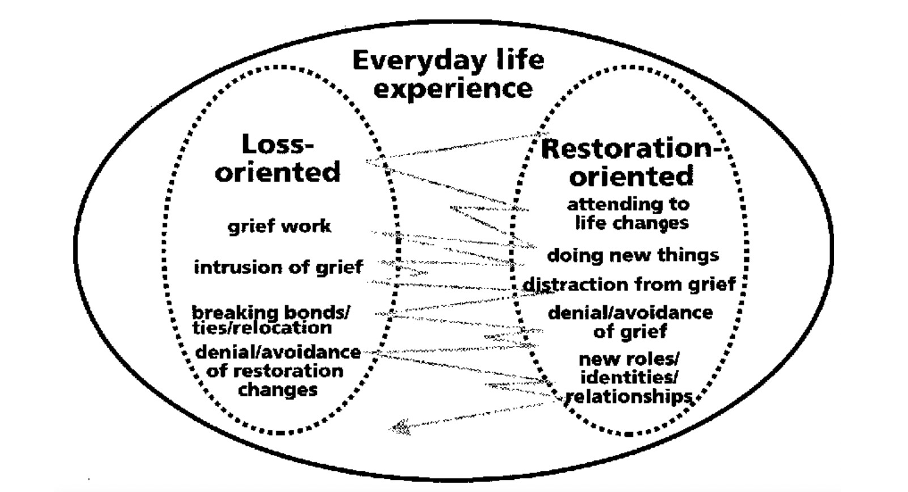

Stroebe and Schut developed the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement in 1999. They reviewed the existing models of grief and identified limitations: existing models only deal with one stressor at a time rather than multiple stressors; bereavement is an intrapersonal process that does not account for interaction with others; and existing models do not look at how the bereaved can grow after a spouse’s death. Their Dual Process Model thus identified two types of stressors: loss- orientated stressors and restoration-orientated stressors.

The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement 1999

Secondary sources of stress and coping include feelings of isolation or trying to cope with carrying out the tasks that the deceased used to do (e.g., cooking, finances etc.). A crucial part of the Dual Process Model is the oscillation between loss-orientated and restoration-orientated stressors. Stroebe and Schut state that healthy grieving is based on the dynamic oscillation between avoiding and confronting the loss. Thus, Stroebe and Schut (1999) and Bonanno (2004) focussed on the individual instead of the loss and adaptation to the loss (as prior theories did).

The Tonkin Growing Around Grief Model

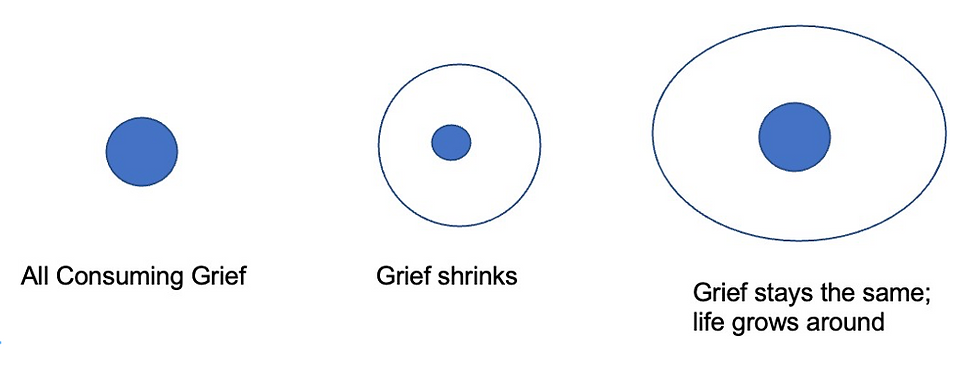

Whilst most believe over time, grief shrinks (Fig 2.2), becoming “neatly encapsulated” in one’s life (Tonkin, 2009, p. 1), Tonkin asserts that grief actually stays the same size, but life grows around it (Fig 2.2). Whilst at times, grief can feel intense, and people operate from within the shaded circle, as time goes by, they increasingly experience life in the outer circle.

The Tonkin Model.

Note:TheTonkin Model(1996).Grief stays the same, and life grows around it.

While the Tonkin model (1996) will not suit all bereaved individuals, it highlights that grief may not diminish or be ‘resolved’ and time does not always heal. Tonkin (2009, p.10) explained, “it relieves [clients] of the expectation that their grief should largely go away. It explains the dark days and also describes the richness and depth the experience of grief has given to their life.” In this way, the bereaved can integrate their loss with their lives and move on without feeling they are being disloyal to the deceased loved one. Many bereavement websites, including the charity Cruse, uses the Tonkin model on their websites, referring to it as the ‘Growing around Grief’ model.

Origins of Continuing Bonds

The theory of grief work was rooted in Freud’s essay Morning and Melancholia (1917/1961), Psychologists and psychiatrists believed that successful mourning could only take place when the mourner “disengages from the deceased, let go of the past, and moves on” (Klass et al., 2018, p.3). This theory continued for several decades even though several researchers reported survivors who did not sever their bond with the dead and were doing well, not to mention that people all around the world from different cultures, religions and spiritual beliefs believed in an afterlife where they would meet their loved one again.

In 1996 Klass et al. published Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief, they did not state that they had developed a new model. Instead, their focus was on clinical practices. This prompted the clinical community to look at the clinical evidence around them, and within a few years, continuing bonds were accepted as a part of grief resolution.

Klass et al. (1996) stated that grieving is never resolved and does not end in recovery or closure; instead, there should be a focus on creating a new relationship with the deceased, given the evidence that maintaining bonds with the dead was not pathological and could even play a positive role in grief (Klass et al., 1996).

Continuing Bonds in the Twenty-First Century

Some of the former models have been updated to reflect these changes: Worden (2013) renamed his Fourth Task of Mourning to “finding an enduring connection with the deceased while embarking on a new life”. David Kessler (2019), an expert on grief who worked closely with Kubler-Ross, added a sixth stage to this model: “Finding Meaning”, giving the following examples: “When my son died, I personally realised I didn’t want to be left in acceptance. I wanted…to make meaning of his life and death” (p. 234). There is a sense that acceptance is passive compared to actively trying to find meaning, searching and discovering new ways of understanding and celebrating the deceased and helping others who are grieving.

Over time, therefore, models of grief appear to have moved away from medical models (characterised by stages and phases) towards a contemporary understanding, where the relationship between the bereaved and the deceased is intersubjective.

Continuing bonds, provides greater scope for considering after-death communications ADC’s) and religious/spiritual experiences (than other theories of grief. The idea of continuing bonds with the dead gained traction, with organisations being set up to highlight and explore the afterlife.

For example, the charitable, secular organisation Forever Family Foundation (FFF) (2022) was established in the early 2000s by psychologist Dr Piero Calvi-Parisetti, whose aim was to reflect on the “unbelievable truth”, putting forward evidence for a “rational belief in life afterlife”. Yet this evidence rarely shapes contemporary grief counselling.

Research indicates in general, mental health services' tools are limited for dealing with grief, and even when interventions are provided, their efficacy is in question (Currier et al., 2008).

Therefore, it is understandable that the bereaved may turn to other, sometimes non-traditional interventions (or alternatively experiences) that help them cope.

Alternative Experiences

Evidence shows that non-traditional interventions and experiences after bereavement, including spontaneous and induced experiences, positively influence grief. In some cases, these “after-death” experiences have been described as “paranormal” or “extraordinary”. One such experience is after-death communications (ADCs), which refers to contact with the deceased (also called “extraordinary experiences” by La Grand (2005).

These experiences include vivid and powerful dreams, hearing voices, sensing the presence of the deceased, and sometimes olfactory and tactile sensations. In addition, there have been cases of electrical communications through the radio or flickering of lights and other unexplainable phenomena like doors opening and closing and butterflies or rainbows appearing (Drewry, 2003; La Grand, 2005; Sanger, 2009).

Drewry (2003, p.3) asserted that “these experiences occur along a continuum of intensity and emotional impact and are common, natural, non-pathological, mostly beneficial and comforting, helpful in facilitating the grieving process, and sometimes extraordinarily spiritually healing to a bereaved individual.”

Research has confirmed that spontaneous ADCs are relatively common (Beischel, 2019; Drewry, 2003; Guggenheims, 1996).

The Guggenheims (2019) researched ADCs for seven years, interviewing 2,000 people living in 50 American states and ten Canadian provinces and collecting more than 3,300 first-hand accounts from people who believed a dead friend or relative had contacted them. The participants ranged from eight to 92-years- old and came from diverse socioeconomic and religious backgrounds. Guggenheim and Guggenheim (2019) conservatively estimated that at least 60 million Americans –20% of the population – had one or more ADC experiences. Some polls indicated that the actual figure is more (43% of the population). ADCs appear to be people's most common form of spiritual experience. ADCs appear when a close emotional bond exists between a griever and the loved one who has passed away, although ADCs can also occur in health professionals or friends.

Adapted from Danielle Baillieu’s doctoral thesis on how contacting a medium affects the grieving process of the bereaved

Comments